#DMTBeautySpot #beauty

With every election season, there are new focal points that center various demographics. Yet, we often hear the same rhetoric regarding Latinx communities on every campaign trail: “Latinos will become the largest minority voting bloc!” “You can’t win The White House without the Latino vote.”

Political contributor Paola Ramos grew tired of hearing the Latinx population be unequivocally referred to as just a headcount — as well as a monolithic, and often stereotyped, identity. “Unless people stop viewing us as statistics and talking points, and until we recognize the multifaceted identities that make up this community, we will not be able to truly step into our collective power,” she tells Refinery29.

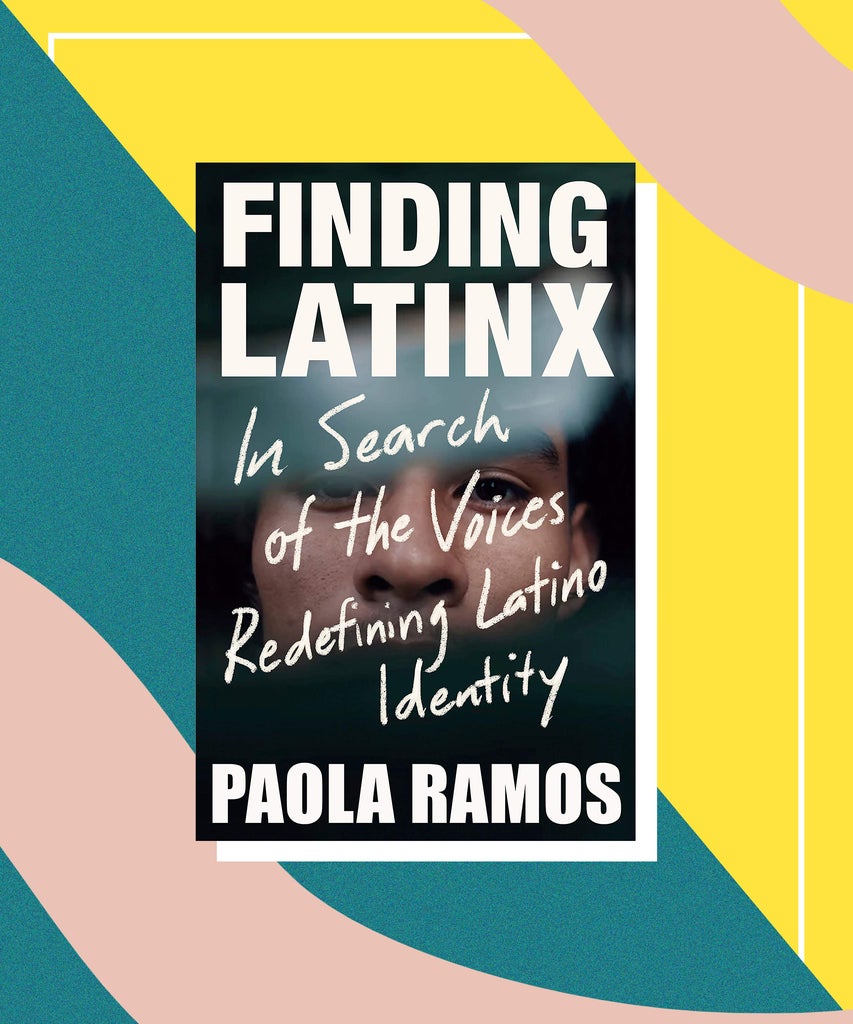

That’s why she has decided to shift the narrative and reshape how we speak of these communities in her upcoming book: FINDING LATINX: In Search of the Voices Redefining Latino Identity. The non-fiction title, that’s set to release on October 20, will document Latinx communities all across the country and dive deeper into the Latino electorate’s power — but not just from a numerical standpoint.

The following exclusive excerpt is from the introduction of FINDING LATINX, where Ramos shares her story of figuring out her place under the umbrella of Latinidad and what the controversial “x” in Latinx has personally signified for her. In the enlightening passages, Ramos dives deeper into the the necessary evolution of language in regards to the term and its historical context. She also explores the diverse realities of this community and how critical it is as a country to look through their lens.

Published with permission from Penguin Random House.

I never really came out.

Until recently.

Even after my loving parents sat me down a couple of times in high school, with open minds yet suspicions of my sexual orientation, I refused to use the word “gay” to describe the way my heart chose to love. Then, when I moved to Washington, D.C., to work in politics, I caught myself cringing when I entered “Hispanic Group Meetings” for networking and idea exchange—not because they weren’t welcoming but because I often felt that I didn’t quite fit in. From afar, when I watched my father’s newscast on Univision, staring at a screen full of women who appeared to have just finished a Latin American beauty pageant, I questioned my own identity as a “Latina.” And even when I gave speeches throughout grad school, my Mexican Cuban heritage was overshadowed by an aggressive Spanish accent I unintentionally picked up during my childhood in Spain. Growing up between Madrid’s progressive environment and Miami’s conservative Cuban community muddled my own political views at a young age. Where, exactly, did I fit in?

Yes, I am queer; I am Latina; I am Cuban, Mexican, and first-generation American. These are words I was not ashamed of saying out loud—but there’s a difference between passive recognition and really owning one’s identity. I openly had girlfriends, checked the “Hispanic” box on school applications, carried three passports, and admired the way my parents’ immigrant journey was central to our being. Yet the truth is that for years I had either blindly danced around these identities or felt I had to choose one over the others. Almost as though I had to wear different hats depending on the rooms I entered or the prejudices I encountered. Safe here, but not so much there. Of course, tiptoeing around these spaces was nothing but a reflection of the immense privilege my citizenship status and light skin granted me in life. Had I been undocumented, or simply a shade darker, I’d carry a target on my back.

Looking back, I realize now that I never really “came out” as my whole self—as fully me. All of this changed the moment the word “Latinx” started rolling off my tongue.

Even though this mysterious term had been tossed around the Web since the early 2000s, I started using it shortly after Donald Trump won the 2016 presidential election. At the time, I didn’t fully understand exactly where that word came from or what it meant—all I knew was that it felt right. It felt more like me. It was a word I couldn’t recognize but one that seemed to know exactly who I was. That addendum, the “x,” set free the parts of myself that had deviated from the norms and traditions of the Latino culture I grew up in in a way that, interestingly, made me closer to, not further from, my own community. A word that wasn’t familiar but one that seemed to tout the uniqueness and diversity that had defined the sixty million Latinos living in the United States. One that felt it aimed to awaken not just a few of us, or half of us, or 90 percent of us—but every single one of us. Even those who had never been seen as “Latino” to begin with. And I wasn’t alone in feeling this.

With Trump’s unforeseen win came a desire for belonging. His victory mobilized millions of people—women, youth, students, black communities, Latinos, immigrants, Dreamers, victims of sexual assault—to take to the streets and fill a void with their voices. People marched with furor, organized their communities, and spoke up in boardrooms and town halls, louder than they had before. Fear induced courage, and the undercurrent of racism that was now fully exposed pushed many of us to embrace inclusion. It was sometime amid this resurged movement that I noticed the word “Latinx” had started to become part of the daily vocabulary of the resistance. Latinx quickly became normalized in my circles, appearing everywhere—protest signs, conference calls, press releases, Twitter feeds, chants, and headlines. “What does Latinx even mean?” some colleagues and I would often ask one another. “Where did it even come from?” We didn’t know, but we kept using it.

There are different answers to that question. But language inevitably evolves with time. A changing vocabulary reflects how a community’s demographics transform the struggles a community faces during different periods in history. Language tells stories, and stories change.

Harvard University fellow Dr. Nicole Guidotti-Hernández points out that the use of the “x” is actually not a new phenomenon. As she writes in one of her articles: “Earliest uses of the ‘x’ come on the front end of Nahuatl-inspired writing of the word Chicano/Chicana as Xicano or Xicana.” In the 1960s and 1970s, the “x” was inserted to “indigenize” Mexican Americans. It was used as a tool to counter Latin America’s colonial history and ensure that indigenous peoples were not erased. Dr. Guidotti-Hernández also provides several historical examples of other ways in which the Latino community pushed back against linguistics in efforts to correct for misrepresentations, gender inequities, or exclusions of nationalities. That’s why, as she underscores, baby boomers fought so hard to institutionalize “ethnic studies” like Cuban American studies and Chicano studies programs on college campuses across America. The boomer generation prioritized nationalities over generalizations. That was the story then: in being able to say “Mexican” or “Guatemalan” over “Latino.” At some point, the word “Latino” was also controversial. Even though it is technically meant to include two genders, the word itself is still masculine. That’s why in the 1990s, people saw feminists rallying to demasculinize the gendered Spanish language, inserting symbols like @ or the neutralized o/a into their daily vocabulary. That was the story then: achieving gender equality and being able to explicitly say, “I am Latina.” Like human beings, language is meant to adapt, not to remain stagnant.

There’s been a long debate centered around the appropriate way to address our community: Do we say “Hispanics” or “Latinos”? Which one do we use? Which one should others use? For decades, the term “Hispanic” was mainstreamed. It was a term coined by a Mexican American staffer in the Richard Nixon administration, Grace Flores-Hughes. As has been reported, one of the reasons Grace advocated for the term “Hispanic” was that it explicitly stemmed from “Hispania,” the Spanish Empire. The word was able to more closely associate the community with its white European colonial past than with its Latin American roots. By embracing the term “Hispanic,” the community’s historic ties to indigenous people, enslaved Africans, and mestizos (the offspring of colonizers and indigenous and/or enslaved Africans) were erased from the picture, washed away as conquistadores swept over the Americas in the fifteenth century. That was the story then: to whiten the community as much as possible. Eventually, however, using the term “Latino/ Latina” became more popular over time, as it more deliberately embraced our Latin American ancestors. (By the way, Grace Flores-Hughes ended up becoming a member of the National Hispanic Advisory Council for Trump.)

Around 2004, coinciding with the Internet’s explosion, Latinx started popping up in online communities of queer Latinos. They were inserting the “x” as a way to express their breaks with gender binaries and welcome gender nonconforming folks into the conversation. There, the initial story was about giving voice to the silenced and often discriminated-against LGBTQ Latinos, a point that was later strengthened by the 2016 Pulse massacre of forty-nine people, most of whom were queer Latinos. By 2018, as Latinx became more colloquial, Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition, officially added it to its pages, defining Latinx as “of, relating to, or marked by Latin American heritage—a gender-neutral alternative to Latino or Latina.” And if you go into Google Trends, you’ll notice a steady rise in searches for the term.

Yet a few years later, people are still wondering what the hell Latinx really means. If Latinx were used just to be more inclusive of queer folks, then perhaps the term wouldn’t cause such controversy and confusion. If the word were used simply to check the “queer” box, then perhaps people would be more okay with it, less afraid of it, more at peace with it. But Latinx is transcending all imaginable borders. All the borders that separated us by race, age, gender, issue, nationality, sexual orientation, and identity. All the ones that divided “us” from “them,” liberals and conservatives. Latinx is not constrained by the explanation given to us on paper by dictionaries, pollsters, and scholars. And that’s why, over the years, people from all different backgrounds kept resurfacing the term, signaling the beginning of the change we were all aching for.

The reality is that for decades that ache for change was inside many of us. It was an ache that craved more unity, acceptance, and inclusion—an ache that simply wanted us to be seen. This ache wasn’t felt just inside the bubbles of activism, D.C. politics, and media—it was a sentiment that lay mostly in the fringes of those very elite spaces: inside homes and out of the public eye. It was in these places that I started recognizing that a lot more people than I thought were not only coming out as Latinx but giving life to that word in a way no dictionary could.

Queer and gender-nonconforming Latinos who had faced discrimination in their own households could relate to that ache. So could Afro-Latinos who had once been told they didn’t “look Latino enough.” And transgender Latinas who were continuously reminded they weren’t “really Latinas,” Asian Latinos who had never been asked about their background, Cuban Americans who wanted to part ways with their family’s long history of conservatism, young Latino men who never found a voice in the criminal justice system, mamis and abuelas who wanted to pave a different path for themselves, Gen Zers who had once been ridiculed for “not speaking Spanish,” midwestern Latinos who felt completely “neglected,” Latinos in the Deep South who said they were “forgotten” by all of us, indigenous migrants whose history had been erased, and millennials in border towns and rural communities who wanted a greater platform than those typically given to those residing in the far edges of the country.

For almost a year, as I prepared to write this book, I hit the road in search of these Latinx voices. I did this before the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the nation and the murders of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and Tony McDade, among others, erupted a massive social movement for justice from coast to coast. But what both of these crises have exposed is exactly what I witnessed on the road months before our nation felt like it was burning: our American system, as it currently stands, is not built for us. And the only way to change it, so that it actually counts for Black and brown people, is by first recognizing who we are.

I crisscrossed the country from west to east, driving through small towns, big cities, urban and rural areas. As I did this, my intention was to rediscover the places I thought I knew, to hear the voices that are often neglected in the back of the room, and to see the hidden faces that lay before our eyes all this time. I met people along the way who identified with many different labels. Some wanted to be called Latinos, others Hispanics. Some wanted to be seen as indigenous peoples, others as white. Some wanted their nationalities to define them, while others wanted their skin color to be the first thing people thought of when they introduced themselves, and many had no idea how to refer to themselves at all. I met people who wanted to be labeled through the eyes of Allah and others through the legacy of the ancient Mayans. And through it all, I understood for the first time that all these seemingly unrelated people—divided by gender, racial, religious, regional, political, and sexual orientation—had more in common than I had ever imagined. While the purpose of this book is to capture a more holistic picture of who we are as a community, one person and a mere 325 pages cannot do justice to our entirety and our richness. My hope, however, is that this book marks the beginning of that portrait.

Unfortunately, if you fast-forward to where we are now, many of the people I interviewed for this book ended up becoming COVID-19’s victims. From undocumented folks to transgender asylum seekers, Afro-Latinos, and essential workers, Latinos are testing positive for COVID-19 at disproportionate rates in almost every state, and in cities like New York, they are dying at higher rates than any other demographic. As I type these words, Latinos are redefining what it means to survive in this country. But this unprecedented pandemic offers the perfect example of why it’s so crucial to look at our community through a Latinx lens. Through it, you comprehend how interconnected our lives and issues are. This crisis is not the wrongdoing of the virus, but the culmination of an intersection of preexisting conditions and fractures, many of which are explored in this book, that have led us to this point.

Introduction: Coming Out as Latinx is excerpted from FINDING LATINX: In Search of the Voices Redefining Latino Identity © 2020 by Paola Ramos. Photography © 2020 by Adam Perez. Published by arrangement with Vintage Books, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

DMTBeautySpot

via https://www.DMTBeautySpot.com

Thatiana Diaz, Khareem Sudlow

0 comments